Difference between revisions of "Scalia, Antonin"

| (2 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | In 1986 Antonin Scalia (1936–2016) was nominated by President Ronald Reagan to serve as associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. Since his appointment, Scalia’s votes have been slightly more favorable to the federal government in cases about federal-state relations than the votes of other justices appointed by Presidents Reagan and George H. W. Bush. However, his distinctive reading of the powers of Congress and the judiciary has challenged the premises of some national supremacist doctrines. Specifically, he has produced unique approaches to preemption and Commerce Clause doctrines, and he has endeavored to protect the jurisdiction of state judiciaries. | + | In 1986 Antonin Scalia (1936–2016) was nominated by President [[Reagan, Ronald|Ronald Reagan]] to serve as associate justice of the [[U.S. Supreme Court|Supreme Court of the United States]]. Since his appointment, Scalia’s votes have been slightly more favorable to the federal government in cases about federal-state relations than the votes of other justices appointed by Presidents Reagan and [[Bush, George H.W.|George H. W. Bush]]. However, his distinctive reading of the powers of [[U.S. Congress|Congress]] and the judiciary has challenged the premises of some national supremacist doctrines. Specifically, he has produced unique approaches to [[preemption]] and [[Commerce among the States|Commerce Clause]] doctrines, and he has endeavored to protect the jurisdiction of state judiciaries. |

| − | In his opinions about federal preemption, which permits federal justices to void state laws when the federal law occupies the same “field,” Scalia has failed to spell out any affirmative constitutional limits to federal power over state policy making. Instead, he has examined precedents and engaged in statutory analysis to determine if there was a clear congressional effort to preempt state law. When he determined that Congress had specifically acted to preempt state authority, Scalia has voted for federal preemption (e.g., ''AT&T Corporation v. Iowa Utilities Board'' 1999). However, when he determined there was sufficient ambiguity in congressional language, he has written opinions (e.g., ''Printz v. United States'' 1997) or voted for the opinions of other justices (e.g., ''United States v. Lopez'' 1995 and ''United States v. Morrison'' 2000) that held the federal government interfered with the independence of state governments as protected by the Guarantee Clause or the Tenth Amendment. | + | In his opinions about federal preemption, which permits federal justices to void state laws when the federal law occupies the same “field,” Scalia has failed to spell out any affirmative constitutional limits to federal power over state policy making. Instead, he has examined precedents and engaged in statutory analysis to determine if there was a clear congressional effort to preempt state law. When he determined that Congress had specifically acted to preempt state authority, Scalia has voted for federal preemption (e.g., ''AT&T Corporation v. Iowa Utilities Board'' 1999). However, when he determined there was sufficient ambiguity in congressional language, he has written opinions (e.g., ''[[Printz v. United States]]'' 1997) or voted for the opinions of other justices (e.g., ''[[United States v. Lopez]]'' 1995 and ''[[United States v. Morrison]]'' 2000) that held the federal government interfered with the independence of state governments as protected by the Guarantee Clause or the [[Tenth Amendment]]. |

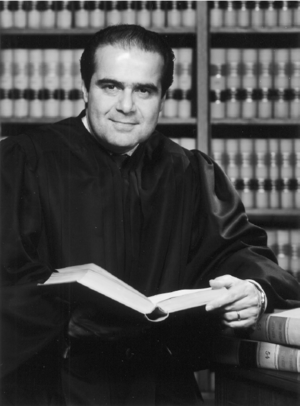

[[File:Scalia, Antonin.png|thumb|Antonin Scalia. Collection, The Supreme Court Historical Society. Photographed by Joseph D. Lavenburg.]] | [[File:Scalia, Antonin.png|thumb|Antonin Scalia. Collection, The Supreme Court Historical Society. Photographed by Joseph D. Lavenburg.]] | ||

| − | Scalia has campaigned to eliminate “negative” or “dormant” Commerce Clause doctrine. This doctrine permits federal courts to void a state government’s legislation that has a discriminatory effect on interstate commerce—even when Congress has not legislated on the subject of state legislation. The doctrine has required the justices balance either the extent of the “facial discrimination” or the “undue burden” of a state regulation of interstate commerce against the value of states’ interests. Scalia’s distaste for balancing and the unbounded discretion it affords judges has caused him to call for a bright legal line—a simple determination of whether a state law discriminates against out-of-state interests. In ''Tyler Pipe Industries v. Washington State Department of Revenue'' (1987), he stated that the justices should not extend any dormant Commerce Clause doctrine and should confine their judgments to “rank discrimination against citizens of other states.” In subsequent opinions, he has elaborated his concern with limiting a dormant Commerce Clause to facial discrimination by a state against commerce originating out of state and to restrictions on state regulation of commerce established in precedent cases (e.g., ''West Lynn Creamery v. Healy'' 1994, ''Oklahoma Tax Commission v. Jefferson Lines'' 1995, and ''General Motors v. Tracy'' 1997). | + | Scalia has campaigned to eliminate “negative” or “dormant” Commerce Clause doctrine. This doctrine permits federal courts to void a state government’s legislation that has a discriminatory effect on interstate commerce—even when Congress has not legislated on the subject of state legislation. The doctrine has required the justices balance either the extent of the “facial discrimination” or the “undue burden” of a state regulation of interstate commerce against the value of states’ interests. Scalia’s distaste for balancing and the unbounded discretion it affords judges has caused him to call for a bright legal line—a simple determination of whether a state law discriminates against out-of-state interests. In ''Tyler Pipe Industries v. Washington State Department of Revenue'' (1987), he stated that the justices should not extend any [[dormant Commerce Clause]] doctrine and should confine their judgments to “rank discrimination against citizens of other states.” In subsequent opinions, he has elaborated his concern with limiting a dormant Commerce Clause to facial discrimination by a state against commerce originating out of state and to restrictions on state regulation of commerce established in precedent cases (e.g., ''West Lynn Creamery v. Healy'' 1994, ''Oklahoma Tax Commission v. Jefferson Lines'' 1995, and ''General Motors v. Tracy'' 1997). |

| − | Scalia has addressed the independent authority of state courts and the nature of federal judicial supremacy, especially in cases about the Eleventh Amendment and Article III of the Constitution. In ''Hans v. Louisiana'' (1890), the Court extended the meaning of the Eleventh Amendment to prevent suits in federal court against a state by its own citizens without the state’s consent. Scalia has accepted congressional authority to develop statutory provisions that selectively override the Hans limitation. However, he dissented when the majority reduced the power of the states to consent to suits. He concluded that Hans served a valuable function in the preservation of state sovereignty and the system of federalism (e.g., ''Pennsylvania v. Union Gas Company'' 1989). When private parties in a suit are citizens of different states, under Article III of the Constitution they can sue in federal rather than state court. Since 1938 the Supreme Court has sought to limit litigants’ efforts to shop for a federal or state forum using legal standards favorable to their case. In several opinions, Scalia has endeavored to further frustrate efforts to manipulate forum selection. | + | Scalia has addressed the independent authority of state courts and the nature of federal judicial supremacy, especially in cases about the Eleventh Amendment and Article III of the Constitution. In ''Hans v. Louisiana'' (1890), the Court extended the meaning of the Eleventh Amendment to prevent suits in federal court against a state by its own citizens without the state’s consent. Scalia has accepted congressional authority to develop statutory provisions that selectively override the Hans limitation. However, he dissented when the majority reduced the power of the states to consent to suits. He concluded that Hans served a valuable function in the preservation of state sovereignty and the system of [[federalism]] (e.g., ''Pennsylvania v. Union Gas Company'' 1989). When private parties in a suit are citizens of different states, under Article III of the Constitution they can sue in federal rather than state court. Since 1938 the Supreme Court has sought to limit litigants’ efforts to shop for a federal or state forum using legal standards favorable to their case. In several opinions, Scalia has endeavored to further frustrate efforts to manipulate forum selection. |

Therefore, in his interpretation of the range of federal and state governmental powers, Scalia has used requirements for congressional clarity in law writing, hostility to balancing of interests by judges, and precedent—all tools of judicial interpretation—rather than a precise constitutional definition or reliance on original texts. | Therefore, in his interpretation of the range of federal and state governmental powers, Scalia has used requirements for congressional clarity in law writing, hostility to balancing of interests by judges, and precedent—all tools of judicial interpretation—rather than a precise constitutional definition or reliance on original texts. | ||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

==== Richard A. Brisbin Jr. ==== | ==== Richard A. Brisbin Jr. ==== | ||

| + | Last updated: August 2017 | ||

| − | SEE ALSO: [[Commerce among the States]]; [[Diversity of Citizenship Jurisdiction]]; [[New Judicial Federalism]]; [[Preemption]]; [[Sovereign Immunity]]; [[United States v. Lopez]]; [[United States v. Morrison]]; [[United States v. Printz]] | + | SEE ALSO: [[Commerce among the States]]; [[Diversity of Citizenship Jurisdiction]]; [[New Judicial Federalism]]; [[Preemption]]; [[Sovereign Immunity]]; [[United States v. Lopez]]; [[United States v. Morrison]]; [[United States v. Printz]]; [[Gonzales v. Raich]]; [[District of Columbia v. Heller]] |

Latest revision as of 01:19, 1 May 2019

In 1986 Antonin Scalia (1936–2016) was nominated by President Ronald Reagan to serve as associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. Since his appointment, Scalia’s votes have been slightly more favorable to the federal government in cases about federal-state relations than the votes of other justices appointed by Presidents Reagan and George H. W. Bush. However, his distinctive reading of the powers of Congress and the judiciary has challenged the premises of some national supremacist doctrines. Specifically, he has produced unique approaches to preemption and Commerce Clause doctrines, and he has endeavored to protect the jurisdiction of state judiciaries.

In his opinions about federal preemption, which permits federal justices to void state laws when the federal law occupies the same “field,” Scalia has failed to spell out any affirmative constitutional limits to federal power over state policy making. Instead, he has examined precedents and engaged in statutory analysis to determine if there was a clear congressional effort to preempt state law. When he determined that Congress had specifically acted to preempt state authority, Scalia has voted for federal preemption (e.g., AT&T Corporation v. Iowa Utilities Board 1999). However, when he determined there was sufficient ambiguity in congressional language, he has written opinions (e.g., Printz v. United States 1997) or voted for the opinions of other justices (e.g., United States v. Lopez 1995 and United States v. Morrison 2000) that held the federal government interfered with the independence of state governments as protected by the Guarantee Clause or the Tenth Amendment.

Scalia has campaigned to eliminate “negative” or “dormant” Commerce Clause doctrine. This doctrine permits federal courts to void a state government’s legislation that has a discriminatory effect on interstate commerce—even when Congress has not legislated on the subject of state legislation. The doctrine has required the justices balance either the extent of the “facial discrimination” or the “undue burden” of a state regulation of interstate commerce against the value of states’ interests. Scalia’s distaste for balancing and the unbounded discretion it affords judges has caused him to call for a bright legal line—a simple determination of whether a state law discriminates against out-of-state interests. In Tyler Pipe Industries v. Washington State Department of Revenue (1987), he stated that the justices should not extend any dormant Commerce Clause doctrine and should confine their judgments to “rank discrimination against citizens of other states.” In subsequent opinions, he has elaborated his concern with limiting a dormant Commerce Clause to facial discrimination by a state against commerce originating out of state and to restrictions on state regulation of commerce established in precedent cases (e.g., West Lynn Creamery v. Healy 1994, Oklahoma Tax Commission v. Jefferson Lines 1995, and General Motors v. Tracy 1997).

Scalia has addressed the independent authority of state courts and the nature of federal judicial supremacy, especially in cases about the Eleventh Amendment and Article III of the Constitution. In Hans v. Louisiana (1890), the Court extended the meaning of the Eleventh Amendment to prevent suits in federal court against a state by its own citizens without the state’s consent. Scalia has accepted congressional authority to develop statutory provisions that selectively override the Hans limitation. However, he dissented when the majority reduced the power of the states to consent to suits. He concluded that Hans served a valuable function in the preservation of state sovereignty and the system of federalism (e.g., Pennsylvania v. Union Gas Company 1989). When private parties in a suit are citizens of different states, under Article III of the Constitution they can sue in federal rather than state court. Since 1938 the Supreme Court has sought to limit litigants’ efforts to shop for a federal or state forum using legal standards favorable to their case. In several opinions, Scalia has endeavored to further frustrate efforts to manipulate forum selection.

Therefore, in his interpretation of the range of federal and state governmental powers, Scalia has used requirements for congressional clarity in law writing, hostility to balancing of interests by judges, and precedent—all tools of judicial interpretation—rather than a precise constitutional definition or reliance on original texts.

After nearly 30 years on the U.S. Supreme Court, Justice Scalia passed away in February 2016. His seat was filled by Justice Neal Gorsuch in April 2017.

| BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Richard A. Brisbin Jr., Justice Antonin Scalia and the Conservative Revival (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996); and M. David Gelfand and Keith Werhan, “Federalism and Separation of Powers on a ‘Conservative’ Court: Currents and Cross-currents from Justices O’Connor and Scalia,” Tulane Law Review 64 (1990): 1443. |

Richard A. Brisbin Jr.

Last updated: August 2017

SEE ALSO: Commerce among the States; Diversity of Citizenship Jurisdiction; New Judicial Federalism; Preemption; Sovereign Immunity; United States v. Lopez; United States v. Morrison; United States v. Printz; Gonzales v. Raich; District of Columbia v. Heller