Difference between revisions of "Jefferson, Thomas"

Morgannoel18 (talk | contribs) |

|||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

==== Luke Perry ==== | ==== Luke Perry ==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Last updated: 2006 | ||

SEE ALSO: [[Hamilton, Alexander]]; [[Federalists]]; [[Louisiana Purchase]]; [[Marshall, John]]; [[Presidency]] | SEE ALSO: [[Hamilton, Alexander]]; [[Federalists]]; [[Louisiana Purchase]]; [[Marshall, John]]; [[Presidency]] | ||

[[Category:Political/Historical Figures]] | [[Category:Political/Historical Figures]] | ||

Revision as of 09:22, 22 October 2017

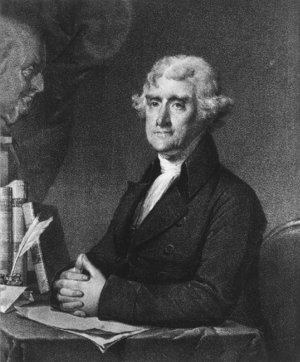

Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States, is an ironic political figure in the development of American federalism. Though Jefferson favored a stricter interpretation of the Constitution than his Federalist predecessors, his presidency dramatically expanded the powers of that office and the national government as a whole.

Jefferson was one of the chief architects of state-centered federalism, first articulated in the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions of 1798. In resistance to the nationalist views of Alexander Hamilton and John Marshall, state-centered federalism operated from the premise that the Constitution was a product of state action because state representatives were responsible for the creation and ratification of the document. In turn, the Constitution protects state power through absolute limits on the powers of national government (Article I, Section 8, and the Tenth Amendment). As a result, a primary focus of citizens and government leaders should be to guard against any expansion of national power at the expense of the states.

Jefferson sought to impose this state-centered perspective through the Revolution of 1800. Once in office, Jefferson reduced expenditures in all branches of government, replaced Federalists appointees with Republicans, and attempted to limit the powers of the Federalist-dominated judiciary. At the same time, each of his terms witnessed monumental expansions in the power of the national government. In 1803, the United States bought over 800,000 square miles of Louisiana territory in one of the largest land deals in American history. With no constitutional power for the national government to purchase new territory, the Louisiana Purchase directly contradicted Jefferson’s governing philosophy. Faced with a unique opportunity to nearly double the country’s land area and to preclude European expansion on the North American continent, Jefferson secured the deal despite his ideological predispositions.

The Napoleonic Wars further complicated Jefferson’s desire for a limited national government. Although the wars created a high demand for goods, Britain, France, and United States all tried to block the others’ trade. Jefferson signed the Nonimportatation Act (1806) and the Embargo Act (1807) to protect American merchants. The embargo prohibited all exports, but since foreign-bound ships were forced to depart empty, the act in effect limited imports as well. Jefferson hoped that resulting economic pressure would convince the British and French to mitigate their maritime policies. Domestically, the national government regulated foreign trade for the first time.

The Louisiana Purchase and Embargo Acts ran directly counter to Jefferson’s desire for state-centered federalism. In theory, Jefferson favored the active protection of state power and the strict limitation of national power. In practice, Jefferson suspended strict constitutional construction in favor of expanding national boundaries and regulating international trade. As a result, Thomas Jefferson is remembered as an ironic figure in the development of American Federalism.

| BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Andrew Burstein, The Inner Jefferson: Portrait of a Grieving Optimist (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1995); Joseph Ellis, American Sphinx: The Character of Thomas Jefferson (New York: Alfred Knopf, 1997); David Mayer, The Constitutional Thought of Thomas Jefferson (Charlottesville: University of Virginia, 1994); and Garrett Sheldon, The Political Philosophy of Thomas Jefferson (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1991). |

Luke Perry

Last updated: 2006

SEE ALSO: Hamilton, Alexander; Federalists; Louisiana Purchase; Marshall, John; Presidency