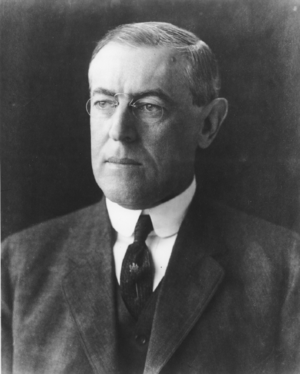

Wilson, Woodrow

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (1856–1924) was elected president of the United States in 1912 and again in 1916. Wilson served the full two terms, although severely incapacitated at the end of his presidency by a stroke he suffered in 1919. Coming into the White House with moderate views regarding the role of the federal government vis-à-vis the states, he moved to a more progressive stance that favored federal programs to regulate business practice, banking, and labor policies. His administration also introduced the federal grant-in-aid program to states, ushering in a new era of intergovernmental relations.

Wilson was educated as a lawyer and academic political scientist. He gained national prominence as president of Princeton University and through his short stint as governor of New Jersey. Picked as the nominee of the Democratic machine bosses in New Jersey, Wilson renounced the party regulars and introduced a progressive agenda that allied him with reformers of both parties. Under his tenure, New Jersey became a model of reform, instituting with Wilson’s support direct primaries, corrupt practices legislation, workmen’s compensation, and regulation of railroads and utilities.

Wilson was elected president in the three-way presidential race of 1912, defeating incumbent president William Howard Taft and former president Theodore Roosevelt, who ran on a third-party ticket. Upon taking office, Wilson avowed to push a program he termed “the New Freedom,” which stressed “special privileges to none” and favored reform of banking and finance, tariffs, and antitrust legislation. The goal of the New Freedom was to insure competition and fairness in society, and was consistent with Wilson’s conservative views on states’ rights and economics. Most of the domestic legislation he favored in his first term, including the Federal Reserve Act and the Clayton Act, did not take away powers thought to rest with the states.

As his presidency progressed, Wilson moved to a more nationalistic domestic agenda. He sent federal troops to Colorado to quell violence between miners and employers (most notably John D. Rockefeller), supported federal legislation to end child labor and to settle a strike by railroad workers, and gave limited support for a constitutional amendment to grant women the vote. It was in the area of agriculture that the most direct influence on federalism can be shown. Led by Secretary of Agriculture David F. Houston, a former university president, the Wilson administration established the federal grant-in-aid approach to provide federal funding support for activities beneficial to the agricultural and rural sectors of society. These included the Smith-Lever Act of 1914, which provided support for the agricultural extension services operating under the aegis of land grant universities, and the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916, which provided federal aid to states to improve highways, a measure favored strongly by rural interests. The latter program, in particular, became a model for later intergovernmental programs, with strict federal requirements placed on the states in the way they staffed, planned, implemented, and funded federal aid highways, a template for federal-state programs that endured after the Wilson presidency ended.

| BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Arthur S. Link, Wilson: The New Freedom (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1956). |