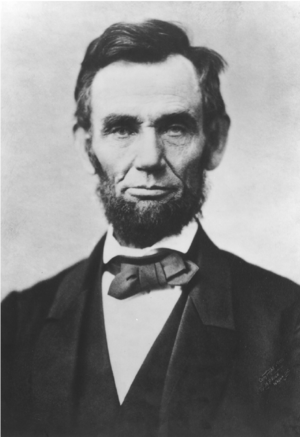

Lincoln, Abraham

Abraham Lincoln, the sixteenth president of the United States, sought to defend the ideals of the Declaration of Independence, maintain order, and preserve the institutions of American government while simultaneously initiating widespread social and political change. Lincoln is remembered as a pragmatic political figure whose rhetoric and actions were highly influential in transforming the United States from a collection of states into one country.

Prior to the Civil War, Lincoln contends that the perpetuation of American government depends on reverence for founding ideals and institutions (Lyceum Speech 1838). Similar to Puritan leaders, such as John Winthrop, Lincoln insisted that the United States must continuously live up to the ideals of the Declaration of Independence. In contrast to Henry Thoreau and Martin Luther King Jr., Lincoln simultaneously insists that all laws, even unjust laws such as slavery, must be obeyed until the law is changed. This mix of reverence for ideals and obeying of laws provided a collective remedy to the problem of individual ambition beginning to divide the nation over slavery. Four years later, Lincoln envisioned two possibilities for holding the American community together: shared interests and a notion of civic friendship (Temperance Address 1842). This constituted an argument for brotherhood as the new focus of political leaders, a main theme of Lincoln’s political thought throughout his life. Dealing with the realities of succession, Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address (1861) clearly states his theory of the federal Union and his duty as president to preserve it.

According to Lincoln, states are bound to the Union by a history of compact dating back to the Articles of Association in 1774. For this compact to be broken, all states must rescind it. If one state or collection of states attempts to withdraw from the union, their actions are considered revolutionary. In turn, Lincoln viewed the Union as perpetual, meaning that the union cannot be legally “unbroken.” As a result, Lincoln’s primary duty as president was to ensure the execution of laws throughout all states, even if faced with violent insurrection. After the Civil War, Supreme Court cases such as Texas v. White (1869) further reconfigured state-centered notions of federalism into a dual theory of perpetual union in which the states and federal government had separate spheres of power. Although the federal government did not completely dominate states, constitutional amendments, civil rights acts, and a highly intrusive, congressionally driven approach to Reconstruction constituted a strong assertion of national authority after the war.

Lincoln and the Republican-dominated Congress adopted many national programs that expanded the national government’s role and authority over domestic policy. Provisions of the Morrill Act (1862) created land grant colleges, which gave states federal lands for the establishment of colleges that offered programs in agriculture, engineering, home economics, and traditional subjects. The transcontinental railroad was authorized on July 1 of that year, subsidizing the construction of a railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean. The railway aided western settlement immeasurably and generated rapid economic growth. Lincoln also created the Department of Agriculture (1862), whose principal duty was to aid farmers through federal programs related to food production and rural life.

Lincoln began his presidency as president of various state citizens and ended his first term as a national figurehead by creating a sense of nationhood through rhetoric, legislative reforms, and military action. Though achieved after his death, Lincoln laid the groundwork for the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments.

| BIBLIOGRAPHY:

David Greenstone, The Lincoln Persuasion (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1993); Henry Jaffa, Crisis of the House Divided (Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Co., 1959); Phillip Shaw, The Presidency of Abraham Lincoln (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1994); and Gary Wills, Lincoln at Gettysburg (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992). |

Luke Perry

Last Updated: 2006

SEE ALSO: Civil War; Declaration of Independence; Morrill Act of 1862; Presidency; Reconstruction; Slavery