Louisiana Purchase

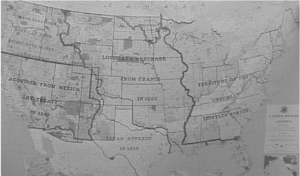

Negotiated in Paris during the spring of 1803, the Louisiana Purchase added approximately 828,000 square miles of French territory to the United States. This resulted unexpectedly from Thomas Jefferson’s attempt to secure trade rights at the mouth of the Mississippi River for American settlers west of the Appalachians. Since the end of the revolutionary war, maintaining access to the Gulf of Mexico was a cornerstone of American diplomacy with Spain, who had controlled the Louisiana Territory since 1762. The 1795 Treaty of San Lorenzo granted Americans unobstructed navigation of the Mississippi and free deposit at the port of New Orleans. But Louisiana was not profitable, and Spain secretly retroceded the colony to France in 1800. Napoleon acquired the region to supply raw materials and foodstuff to Saint-Domingue (present-day Haiti) and to reestablish a foothold in North America. Surprised and threatened by the news in 1801, Americans feared that Napoleon would rescind the Treaty of San Lorenzo. While Federalists called for an armed seizure of the gulf coast, Jefferson sought a diplomatic solution.

In April 1803, Jefferson dispatched James Monroe to join Robert R. Livingston, the American minister to France, to attempt to purchase New Orleans and the southern portions of Mississippi and Alabama (known as West Florida), or at least reaffirm American navigation and deposit rights. Monroe arrived with a $2 million appropriation and authorization to offer as much as $10 million for the desired land. In the year prior to the meeting, the successful revolution in Saint Domingue and the disintegration of peace in Europe caused Napoleon to abandon his ambitions in the Americas. Surpassing all expectations, Monroe and Livingston were offered the entire Louisiana Territory and struck a bargain that exceeded their mandate. They agreed to pay $15 million—$11.5 million in cash and $3.5 million in annulled debts—for a huge tract bounded to the south by the Gulf of Mexico, to the east by the Mississippi, to the west by the Rocky Mountains, and to the north by British claims in Canada. The United States would double in size for about 4 cents per acre.

Debate about American expansionism arose immediately. Federalists questioned the legality of even making such a purchase, while Jefferson had to loosen his usually strict interpretation of the Constitution to accept the arrangement. Congressional approval came on October 20, 1803, setting a precedent for future expansion. Boundary disputes with Britain and Spain were not resolved until the Convention of 1818, and the 1819 Adams-Oníz Treaty clarified the northern, southeastern, and western borders. Internally, Congress debated how to incorporate the territory and its people into the national polity. Drawing on the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 and the creation of the Mississippi Territory in 1798, Congress organized districts and installed a territorial government in 1804. In 1812, Louisiana joined the union as the first of 14 states once entirely or partly contained in the original purchase.

| BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Peter J. Kastor, Nation’s Crucible: The Louisiana Purchase and the Creation of America (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2004); and Jon Kukla, Wilderness So Immense: The Louisiana Purchase and the Destiny of America (New York: A. A. Knopf, 2003). |

Robert Lee

SEE ALSO: Jefferson, Thomas