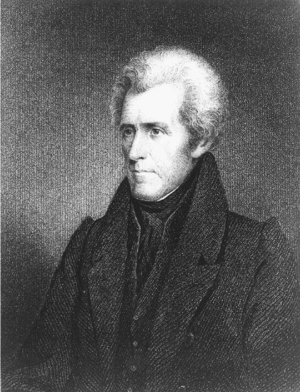

Jackson, Andrew

Andrew Jackson’s (1767–1845) personality and two presidencies remain mired in controversy. Admirers saw him as embodying the democratic virtues of the West, a rough-and-tumble backwoodsman, Indian fighter, hardworking farmer, tenacious general, and defender of women—the logical culmination of the triumph of democratic values in the United States. His detractors portrayed him as uneducated, violent, and vengeful, a slaveholder and Indian hater, and the personification of the politics of mediocrity. He moved to Charleston while still a teen, where he imitated the manners of the gentry, indulging in gambling, horse racing, and cockfighting. He also studied law, and shortly after admission to the bar settled in Nashville, Tennessee, where he went to work for creditors, engaged in land speculation, and took up politics. Among the offices he held were U.S. attorney, congressman, and justice of the Tennessee Supreme Court—all before age 31. Also an army general, he became a national hero following his victory at the Battle of New Orleans in 1815.

Jackson believed that the election of 1824 was stolen from him by a deal between rivals John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay. That campaign and its 1828 successor were characterized by vicious mudslinging by both camps, reflecting a surge in popular participation in politics. Jackson’s victory in 1828 was part of a democratic trend in politics inspired by the economic panic of 1819, which many blamed on the tight money policies followed by the Bank of the United States. Voter apathy gave way to renewed interest in the issues that directly affected them: monetary policy, eastern dominance, high tariffs, and public land policy. These concerns led to the abolition of property qualifications for voting, the end of the caucus system, greater numbers of elected officials, and the disestablishment of churches.

The guiding principle of the Jackson presidencies was that government intervention on behalf of the interests of the rich had to be stopped. This so-called money power was resented particularly in the West, where it was regarded as an alien force controlled by wealthy Easterners. The Jacksonian movement set its sight on annulling the marriage between big business and government, a relationship that spawned government favoritism toward the wealthy. Jackson saw his vetoes against the rechartering of the Bank of the United States, the federal purchase of stock in a Kentucky turnpike corporation, and the Marysville Road Bill as part of a broader struggle between the special privileges of the business community and the common good of the rest of society over who should control the state.

Though ideologically the Jacksonians were antistatist and paid homage to the Jeffersonian notion that the best government was one that governed least, they believed that the exercise of power on behalf of the community by a government consisting of “patriotic” people—the majority of average citizens—was permissible and necessary. Hence Jackson supported the Supreme Court’s decision upholding the right of the state of Massachusetts to construct a free bridge over the Charles River at the expense of a privately owned bridge. The proper role for the state for Jackson depended on who controlled it. He believed that in promoting the happiness and prosperity of the community, the government never intended to curtail its power to implement those goals. Hence Jackson’s position on the role of state intervention is not completely at odds with that of arch-Federalist Alexander Hamilton, who conditioned his support for wealthy entrepreneurs by using the federal government to channel their financial rapaciousness so as to benefit the nation and to speed up economic growth. To leave the business class entirely on its own, said Hamilton, “may be attended with pernicious effect.” Jackson’s rejection of the Federalist vision as articulated in Henry Clay’s American System rested on his (mistaken) conviction that Federalist support of protective tariffs, the Bank of the United States, and internal improvements was meant solely to advance the interest of a privileged business class. Ironically, despite his antistatist credo, when Jackson left office the power of the federal government, especially its executive branch, was stronger than ever. By appealing to the people over the heads of Congress in his bank veto message and ending the legislative branch’s power to select presidential candidates by “King Caucus,” Jackson dramatically enhanced the powers of the presidency, leading his enemies to dub him “King Andrew.”

Despite his aversion to state power, Jackson remained a staunch nationalist, dating from the American Revolution, when he was captured and mutilated by British troops at age 14, and witnessed the imprisonment and death of his two brothers and mother. Not surprisingly, then, when South Carolina claimed it could nullify the 1828 so-called Tariff of Abominations, Jackson asked Congress to authorize the federal government to use force, if necessary, to bring South Carolina back into the fold. Jackson’s nationalism also played a significant part in his unwillingness to accept the Supreme Court’s recognition of Cherokee sovereignty in Worcester v. Georgia, and in his willingness to allow state officials to override federal support for Cherokee land claims. He eagerly signed the Indian Removal Act, forcing the Cherokee Nation to evacuate its ancestral lands and march on the Trail of Tears.

In the realms of morality and religion, Jacksonian Democrats tended to be the party of laissez-faire, and in contrast to the Federalists, were averse to government involvement in social and humanitarian reform. Jackson condemned public schooling for usurping parental responsibility, had few objections to slavery, and despised abolitionists.

While historians continue to argue over whether the main conflict in the Age of Jackson was between rich and poor (farmers and workers) or between old money and new, or was primarily a sectional dispute—West versus East—there is consensus that while loosening the hold of the Virginia dynasty, Jackson did not effect a political or social revolution. Jackson’s call for rotating political offices—“in a country where offices are created solely for the benefit of the people no man has more intrinsic right to official station than any other”—was not implemented in practice. Hence, while the common man may have felt he was participating in government, for example, by being invited to Jackson’s Inaugural, there was no significant redistribution of wealth under his presidencies, and despite a seeming deference to the common man, the uncommon men (of Jackson’s “Kitchen Cabinet”) continued to run things.

| BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Richard Hofstadter, “Andrew Jackson and the Rise of the Capitalism,” in The American Political Tradition (New York: Vintage Books, 1973); Edward Pressen, Jacksonian America (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1985); Robert Remini, The Life of Andrew Jackson (London: Penguin Books, 2001); Arthur Schlesinger, The Age of Jackson (New York: Mentor Books, 1945); Charles Sellers, The Market Revolution: Jacksonian America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990); and Harry L. Watson, Liberty and Power, The Politics of Jacksonian America (New York: Hill and Wang, 1990). |

Harvey Asher

SEE ALSO: Abolition; Adams, John; Admission of New States; Charles River Bridge Company v. Warren Bridge Company; Clay, Henry; Elections; Federalists; Hamilton, Alexander; Internal Improvements; Native Americans; Slavery; Sovereignty